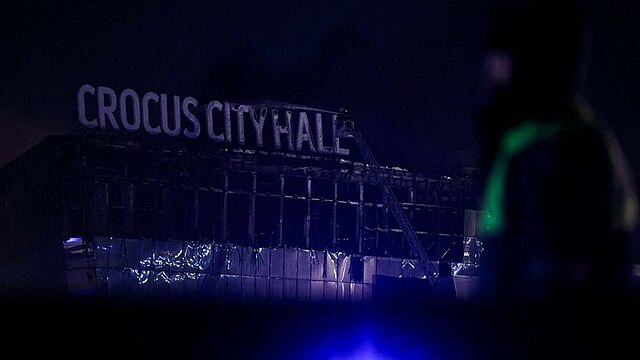

Russian authorities have charged four Tajiks for their involvement in the deadly terrorist attack at the Crocus City Hall in Moscow on March 22 that cost the lives of at least 140 people. The men were allegedly recruited by Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP), a regional branch of Islamic State. The events in Moscow have highlighted Tajikistan’s struggle with radicalisation.

On the evening of 22 March, gunmen attacked the Crocus City concert hall near Moscow, killing at least 140 people. The following day, TASS reported that 11 people were arrested for their involvement in the attack. Among them were four citizens of Tajikistan, who later appeared in court with signs of torture. Although many details about the attacks are still unclear, experts suggest the involvement of Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP), a regional branch of Islamic State that is actively recruiting among Tajiks.

The events at the Crocus City Hall have spurred a xenophobic backlash in Russia. Eurasianet reported about a 35-year old Tajik who was summarily evicted from his home in Moscow following the attack. According to the independent Russian media outlet Meduza, Russians have started refusing taxis with Tajik drivers. Moreover, security services are increasingly profiling people based on ‘Asian features’. Not only Tajiks are affected by the current wave of xenophobia in Russia. Kyrgzystan has urged its citizens not to travel to Russia and 24.KG writes that forty Kyrgyz were denied entry into the country at a Moscow airport.

ISKP and Tajikistan

Hours after the attack, Islamic State (IS) claimed responsibility for the attack through its central communication channels on Telegram. Later, the terrorist group published photos of the perpetrators and first-person footage of the attack on Telegram to substantiate their claim. However, analysts point to Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP) as the main suspect. This regional affiliate of IS was founded back in 2015 in Afghanistan and initially recruited dissenters from the Taliban.

Khorasan refers to the idea of Greater Khorasan, the historical region that extends from eastern Iran to Badakhshan in Tajikistan, and from Tashkent to southern Afghanistan. ISKP hopes to establish a caliphate there, with the ultimate goal of expanding it beyond the region. After the fall of Kabul in 2021, the Taliban is engaged in a counterinsurgency against ISKP. Regularly, ISKP carries out terrorist attacks in Kabul and elsewhere in the country. The Diplomat writes that these attacks are primarily executed by ethnic Tajiks.

Read more on Novastan: The Taliban at the gates of Central Asia: what are the consequences?

Since its formation, ISKP has forged alliances with militant Islamist groups in Central Asia and started recruiting volunteers there as well. Edward Lemon, a researcher specialising in Central Asia and president of the Oxus Society, claimed on X that “while the threat within the country has been minimal, Tajikistan had the third highest per capita recruitment to Syria in the world, it’s citizens took on key roles in IS and have been involved in attacks or foiled plots in Iran, Afghanistan, Germany and Turkey this past year.” There is little information on the number of Tajiks recruited into its regional affiliate, ISKP.

Indeed, on July 6 last year, German news website Tagesschau reported that seven men from Central Asia were arrested in the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia for alleged membership of ISKP, as well as for preparing a terrorist attack in Europe. They included five Tajiks, one Kyrgyz and one Turkmen. The arrests were the result of a joint investigation by the German and Dutch authorities. In the Netherlands, a further two suspects were apprehended: a man from Tajikistan and a woman from Kyrgyzstan.

Radicalisation in Tajikistan

Research has shown that Tajik militants are being recruited among Central Asian migrant workers in Russia, as well as in impoverished communities in Tajikistan itself. Tajikistan is highly dependent on the money that is being sent home by the migrant workers abroad. The World Bank estimated that 51 per cent of the country’s GDP consists of remittances. But faced with xenophobia, racism and marginalisation in Russia, Islamic fundamentalism makes for an appealing alternative.

Mélanie Sadozaï, a researcher specialising in the Tajik-Afghan border, explained to Novastan: “There are many reasons why these individuals are recruited: search for a better life, rejection of the state and its institutions, desire to practise Islam without discrimination, financial motivations, denunciation of Russian involvement in Syria, where IS itself is based, etc.” According to Sadozaï, “the decision to join IS is often more complex than a deepfelt belief in the radical Islam advocated by the terrorist group.“

That said, radicalisation can also be a reaction to Tajikistan’s ultra-secular politics. Dushanbe is currently implementing a “National Strategy for Combating Extremism and Terrorism.” As part of this strategy, the government has adopted 35 laws aimed at restricting activities described as “terrorist”. This legislation has led to restrictions on individual and religious freedoms and freedom of association. The documents are rooted in the Tajik government’s desire to combat the practice of Islam in general, not Islamic extremism alone.

The politicisation of extremism

The problem of radicalisation is exploited by the Tajik government to push through its secular political agenda and silence opposition. As reported by the Institute for War and Peace, women and minors in Tajikistan are not allowed to pray in mosques. Similarly, the wearing of hijabs by women and beards by men is often considered extremist. The fight against terrorism therefore has a major impact on the role of Islam in society.

Practising Muslims are under greater scrutiny. Since the repression of a series of demonstrations in May 2022 in Gorno-Badakhshan, an autonomous region that makes up the eastern half of Tajikistan, the local Shiite minority has been further affected by restrictions on freedom, particularly in religious matters.

Read more on Novastan: In Tajikistan, repression continues

According to Roustam Azizi, a member of the Islamic Council of the Presidency, the definition of the terms ‘extremism’ and ‘terrorism’ is vague. This makes it possible to classify various opponents of the regime, such as political dissidents, but also journalists and lawyers, as ‘terrorists’. In 2023, for example, the independent news outlet Pamir Daily News was declared ‘extremist’.

Considering the repressive policies of the Tajik government, terrorist activities involving Tajik nationals are primarily diffuse and delocalised. In other words, they take place abroad. However, the authorities’ harsh approach feeds into religious and political extremism. According to Mélanie Sadozaï, Dushanbe is “tightening constraints and security measures against religious practices and potential rivals or destabilisers of the current regime, which only serves to fuel frustrations that can take the form of terrorist attacks“.

Tajik-Afghan security cooperation

The border between Tajikistan and Afghanistan is sometimes mentioned as a potential corridor for jihadists. Sadozaï, however, states that there is no evidence for this. On the contrary, Dushanbe seems not very concerned about the situation along the border. For example, the researcher points to the fact that in September 2023, cross-border markets were reopened for commercial activities.

Yet, since the Taliban takeover in 2021, there are no formal diplomatic relations between Tajikistan and Afghanistan. The Tajik government remains the Taliban’s fiercest critic. This has to do with the Taliban’s support for Jamaat Ansarullah, a Tajik Islamist militant group operating from Afghan Badakhshan, just across the border with Tajikistan.

At the same time, the Tajik government cooperates with the Taliban authorities in Kabul on certain security issues. For both Dushanbe and Kabul, ISKP is a common enemy. Mélanie Sadozaï states that the terrorist group “undermines the credibility of these regimes in terms of their ability to maintain the security of the countries they govern“. Yet, ISKP is no cross-border organisation, but a transnational terrorist group. Most Tajik militants that join ISKP do so via Russia, Sadozaï concludes.

Julian Postulart, Judith Robert

Editors of Novastan English & Novastan French

For more news and analysis from Central Asia, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Telegram, Linkedin or Instagram.

Moscow attacks highlight Tajikistan’s radicalisation problem

Moscow attacks highlight Tajikistan’s radicalisation problem