Iran and Uzbekistan’s joint infrastructure projects are picking up steam despite the pandemic. A first working meeting between India, Iran and Uzbekistan in mid-December 2020 once again underlined the commitment of all parties. Above all, the deep-water port in Chabahar in southern Iran stands as a potential gateway to world trade for the Uzbek economy.

This article was originally published on Novastan’s German website on 19 January 2021.

The port of Chabahar, in southern Iran, is at the heart of a new Eurasian infrastructure initiative. Rail and transport links to and from the port are intended to better connect Central Asia and especially Uzbekistan and Afghanistan to international freight traffic. The new routes would significantly reduce previous transport times as well as costs and could contribute to an economic upswing in the Central Asian republics.

On 14 December 2020, a first trilateral working meeting took place between Uzbekistan, Iran and India. Prior to this, Iran and Uzbekistan had already held several bilateral meetings and visits. The latest meeting was co-chaired by India’s shipping minister Sanjeev Ranjan, Uzbekistan’s deputy minister for transport Davron Dehkanov and Iran’s deputy transport minister Shahram Adamnejad. The focus was on the three countries’ relations under the Ashgabat Agreement, which came into force in 2016, and on the Chabahar infrastructure project.

Want more Central Asia in your inbox? Subscribe to our newsletter here.

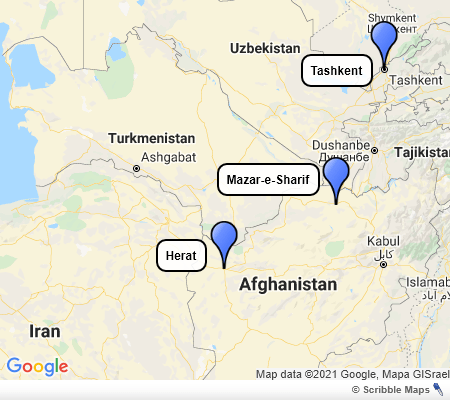

According to Adamnejad, Uzbekistan, as the most populous country in Central Asia, has an interest in expanding its logistics and transport capacity and creating additional links to drive its economy forward. The Ashgabat Agreement provides for cooperation in the transport sector between Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Iran, Oman and, since February 2018, India. It also connects with International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), a transport route stretching from Russia to India. From the Uzbek side, rail links are already in place in the direction of northern Afghanistan’s Mazar-e Sharif, testifying to Tashkent’s ambitions. Tajikistan is also connected to this link, which would run towards Mashhad in north-western Iran and from there on to the Persian Gulf.

Iran’s Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA) reports that Uzbekistan’s Dehkanov praised the facilities of the port of Chabahar, pointing out that in view of the operational capabilities, equipment and strategic position of the port, the formation of a joint working group would be pushed forward as soon as possible.

Iran as a future hub for trade with Uzbekistan and Central Asia

In early May 2019, Iran’s special envoy Kamal Kharazi visited the Uzbek capital for bilateral talks. Joint and regional issues were discussed, such as the construction of the rail link between the Afghan cities of Mazar-e Sharif and Herat, as well as other aspects of the Chabahar project. Both sides agreed to increase the container transport volume on this route.

Tashkent sees the connection via Iran as the economically most profitable and shortest link to the world markets. Conversely, Tehran sees the connection via Uzbekistan as the strategically most important and shortest transit route to China and East Asia. However, the overall trade volume has been manageable so far, not least because of Iran’s economic situation and the coronavirus pandemic.

Another possible train route is from Chabahar to resource-rich central Afghanistan, which would also enable a connection to Kabul. The project, financed and driven mainly by India, is partly in competition with China’s Belt and Road Initiative. With INSTC, India is trying to bypass the overland route via Pakistan and at the same time create an alternative to China’s Belt and Road network for the Central Asian states. China’s increasing dominance and market strength in Central Asia is prompting New Delhi to create alternatives and to dig deeper into its pockets. The expansions of water, rail and road networks planned within the framework of INSTC and by the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative would almost halve the transport routes to the countries of Central Asia and make Iran a future hub for trade with the region.

Bilateral relations and regional goals

At the end of July 2020, a virtual conference was held between the Uzbek minister of investment and foreign trade, Sardar Omar Zagov, and the Iranian vice president for economic affairs, Mohammad Nahavandian, as reported by the Tehran Times. The Iranian side announced that the trade volume between Uzbekistan and Iran had increased by 40 per cent in 2019. Sardar Omar Zagov underlined Iran’s important role as a trade partner for Uzbekistan, stressing the ties between the countries: “We believe that geographical proximity and spiritual commonalities are a good opportunity that can be used to increase the level of economic relations between the two countries“

Tashkent said it welcomed the presence of Iranian investors and engineering companies in economic and development projects in the country. It is also interested in expanding scientific and technological relations. Shortly after the conference, the chairman of the Chabahar Free Trade-Industrial Zone Organisation announced an agreement with Uzbekistan: the country will trade agricultural products and minerals with India via Chahabar.

Both Iran and Uzbekistan are located in strategically important positions in the region and pursue geopolitical goals and interests in this regard. Uzbekistan strives for good neighbourly relations and tries to ensure stability and security in the entire Central Asian region. In doing so, it insists on neutrality in the conflict between Tehran and Washington. At the same time, the Uzbek government is trying to work towards strengthening relations between Iran and important regional actors such as Russia, China, Turkey and India.

Read more on Novastan: Russia commits to railroad corridor China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan

Iran is striving to address the situation in Afghanistan in cooperation with neighbouring countries and to transform it to its own advantage. Through joint projects, it is ensuring it will continue to play the role of a gateway to Central Asia, including as a transit corridor for oil, gas and other goods.

Although the US State Department plans to exempt the port in Chabahar from sanctions, the project has recently developed more slowly than planned due to the coronavirus pandemic and the American sanctions strategy of “maximum pressure”. The exemption is granted because of the project’s potential economic benefits in Afghanistan and India. The slowdown of the region’s economic plans is consequently also hampering the further development of the Uzbek economy.

A good relationship between Iran and the Central Asian countries is becoming increasingly important for Tehran in view of the continuing American sanctions. With a new president of the United States and a possible relaunch of the so-called nuclear deal of the 5+1 group, it will become clear whether Iran’s political position will once again move closer to the West. If future negotiations do not work out, Iran’s eastern ties, which have been strengthened since the collapse of the nuclear negotiations due to US withdrawal from the treaty, could develop further.

Progress also depends on future US policy

What is certain is that Iran is in any case becoming increasingly connected to its eastern neighbours. Uzbekistan in particular is counting on future cooperation to gain access to the Indian Ocean. Trade relations and points of contact already exist between the two countries in multilateral formats such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, in which Iran has observer status.

The biggest obstacle to economic traffic between Uzbekistan and Iran continues to be the American sanctions, which both paralyse the Iranian economy and indirectly slow down infrastructure projects such as Chabahar. A serious conflict between Tehran and Washington would also partially affect the transit routes for Uzbek goods. Thus, a reopening of the nuclear negotiations would be in the interest of the government in Tashkent. With Joe Biden becoming president of the United States on 20 January, expectations are rising both in Tehran and Tashkent. If they are fulfilled, economic and political relations between Iran and Uzbekistan could reach a new level of cooperation.

Darius Regenhardt

Novastan Deutsch

For more news and analysis from Central Asia, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Telegram, Linkedin or Instagram.

Uzbekistan: towards greater cooperation with Iran?

Uzbekistan: towards greater cooperation with Iran?