Prior to his resignation as president of Kyrgyzstan on 15 October, Sooronbay Jeenbekov had announced an agreement with Russia on the railroad project between China, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan.

This article was originally published on Novastan’s French website.

In an interview with the radio station “Birinchi Radio” on 19 September, barely a month before his resignation, President Jeenbekov had confirmed Russia’s participation in the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railroad project. “We have reached an agreement at the highest level with Russia on its participation in this project. Active negotiations are currently underway between China, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Russia, in the format of three plus one,” the then president said.

Want more Central Asia in your inbox? Subscribe to our newsletter here.

Accordingly, Russia is to be part of any further negotiations on the railroad corridor. This could advance the 25-year-old project, especially as the coronavirus pandemic seems to be giving it new momentum. The corridor would allow for goods to be transported from China to Europe more quickly.

On 25 November 2019, the Russian news agency Regnum had already reported that Russia was politically interested in the project and had already invested the equivalent of three million US dollars. Russia is even considering direct financing of, for example, the construction of the necessary infrastructure.

No agreement over Kyrgyz route

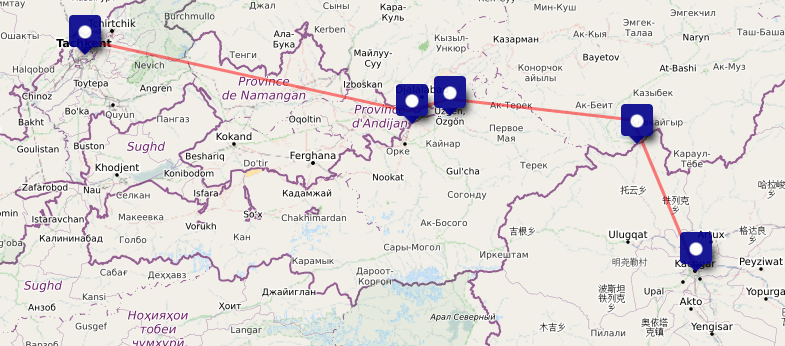

The railroad corridor China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan aims to connect Chinese railways with the Uzbek capital Tashkent. This rail link would also be an opportunity for greater connection to the rest of the world for Central Asian networks.

The route has varied considerably over the years but now seems at least partially settled, as reported on the former website of Kyrgyzstan’s national railway service. It begins in Kashgar in China’s Xinjiang, the Uyghur Autonomous Region, and runs for about 165 km to the Torugart Pass. This part of the line is already in place but goods arriving in Kyrgyzstan then cross the country in lorries, as there is no railway on the Kyrgyz side of the pass.

A section of about 250 km to the west to the Fergana Valley in Uzbekistan has not yet been built. Kyrgyzstan and China are having difficulties agreeing on the exact route over the Kyrgyz territory. According to current plans, the route would pass through the cities of Ösgön and Kara-Suu, north of Osh, before finally reaching Uzbekistan.

China seeks access to Uzbekistan’s oil fields

China, the initiator of the project, seeks to expand the Central Asian railway infrastructure to Afghanistan, Iran, Turkey, and Europe in the long term. In the short term, the construction of the line would also give China better access to the Mingbuloq oild field in Uzbekistan.

As Bruce Pannier reported in 2017 in an article for Radio Free Europe, the Mingbuloq production site was only opened when the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) signed an agreement to develop the oil field in October 2008. CNPC estimates that there are more than 30 million tons of oil in the region and that Mingbuloq could produce around 4000 barrels per day in the long run. Although this is far below China’s daily consumption, it could be extracted very close to China’s territory.

A much-delayed project

The China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railroad project was originally launched 25 years ago, a few years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, but it was not implemented until October 2020. The reasons for this are manifold.

The first technical problem lies in the gauge of the tracks. The railroads in Kyrgyzstan uses a gauge of 1.52 metres, against 1.435 metres in China. Failure to reach agreement would require expensive re-gauging during the journey.

Kyrgyzstan has delayed the project several times, too. As Bruce Pannier points out in another article for Radio Free Europe, Kyrgyzstan is reluctant to do its part of the work for financial and geographical reasons. In 2017, Kyrgyzstan’s then President Almazbek Atambayev declared that there was no need for a railroad line that did not stop in Kyrgyzstan. At the same time, he instead proposed a longer route that would connect smaller cities in the north of the country. Including tunnels and bridges, this connection would increase the overall costs by 1.5 billion US dollars (£1.1 billion), an unreasonable sum given the current budget of 1.3 billion dollars (£990 million), mainly paid for by China. Russia’s entry could enable renegotiations in favour of Kyrgyzstan.

As the Kyrgyz news portal Times of Central Asia points out, despite all efforts to ensure cooperation between governments, the various border conflicts since 2017 have also been a further obstacle to development.

Uncertain Russian interests

In view of the disagreement among the three partners, it is not clear to what extent the entry of a fourth country can revive the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railroad project.

Above all, one question remains: why would Russia contribute its expertise and resources if it does not seem to derive any direct economic benefit from the project? As an alternative route to Beijing, the project could provide strong competition to Russia’s current monopoly for transit traffic of Chinese freight towards Europe.

Clément Clerc-Dubois

Novastan.org

Translated by Magnus Obermann

Russia commits to railroad corridor China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan

Russia commits to railroad corridor China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan