Over the past six weeks, hundreds of thousands of viewers have tuned in to Dutch public broadcaster VPRO to watch the new docuseries “Along the new Silk Road”. For most people in the Netherlands, this show is their first introduction to Central Asia. But as its title suggests, the documentary is dotted with orientalist stereotypes about the region. A critical review of a missed opportunity.

The opinions expressed in this review are those of the author.

Since its first broadcast on public television, the Dutch docuseries “Along the new Silk Road” has attracted hundreds of thousands of viewers. So far, this six-part series has averaged over one million people per episode. Even for a primetime show in the Netherlands, these numbers are impressive.

Most notably, on Sunday March 19, the series’ third episode attracted more viewers than the paid-only live coverage of the Ajax-Feyenoord match – the country’s main football rivalry.

The show is presented by two popular Dutch documentary makers: Ruben Terlou and Jelle Brandt Corstius. Both have made successful docuseries in the past. Whereas Terlou has had a lifelong passion for China as a photographer and speaks Mandarin fluently, Brandt Corstius is a former Russia correspondent for a Dutch quality newspaper.

Central Asia as terra incognita

Interestingly, neither Terlou nor Brandt Corstius are experts on Central Asia. Brandt Corstius acknowledges this by stating that he only knows the region insofar as “it was part of the Soviet Union”. Terlou admits that he “always dreamt of following the magical Silk Road”. During his time in China, he saw the growing importance of China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Read more on Novastan: China in Central Asia: Fact-checking and myth-busting

Considering both presenters’ respective backgrounds, it comes as no surprise that “Along the new Silk Road” is not a documentary about Central Asia. Instead, the series tells a story of foreign influence, competing interests and geopolitical rivalry. This Great Game-like narrative reduces the region to little more than a great powers playground.

By depicting Central Asia as some sort of mysterious terra incognita, “Along the new Silk Road” cannily taps into pre-existing orientalist ideas about Central Asia in the Netherlands. Often these depictions are based on stereotypical and colonialist perspectives of eastern cultures, framing them “as extremely different and inferior, and therefore in need of Western intervention or ‘rescue’”.

Orientalism, voyeurism and white saviourism

In “Along the new Silk Road”, orientalism often takes the form of voyeurism. For example, when discussing bride kidnapping in Kyrgyzstan, the makers’ intentions of doing so remain unclear, other than illustrating the backwardness of such practices.

Even worse is that by discussing such controversial and complex topics without providing any context, the documentary makers parasitise on the victims’ grief to imbue their audience with a sense of white saviourism. It is not difficult to see that such manifestations of orientalism help justify (neo)colonialism.

But the most obvious orientalist reference is undoubtedly the series’ title. This cliché choice alludes to the image of exotic caravans traversing inhospitable deserts and high mountain passes. This imagined geography of Central Asia degrades the region to a simple trading corridor, rather than a place of interest in its own right – a criticism that has prevented some experts from using the concept of “Silk Road” altogether.

The role of Dutch and Western media

But the series’ presenters are not the only ones to be blamed for this orientalist misrepresentation. In part, producer VPRO simply caters to the limited knowledge on Central Asia in Western Europe in general.

Most people in the Netherlands would likely have a hard time pinpointing Central Asia on a map, let alone identify individual countries. For those who can, the region is often little more than a far-away, post-Soviet wasteland ruled by despotic presidents.

Dutch media, like most other news outlets, have contributed to creating this image. Current affairs in Central Asia were long covered by correspondents based in Russia, the region’s former coloniser. For most media outlets, this was standard operating procedure until the start of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. Yet, as the war escalated, many Western journalists were forced to leave Moscow.

Read more on Novastan: Kazakhstan’s gradual divorce from Russia

This exodus freed up resources to report on the wider implications of Russia’s war in Ukraine. Dutch media have paid considerable attention to the recent geopolitical repositioning of former Russian colonies, such as in Kazakhstan. And interest in the region is not only limited to so-called high politics.

The colonised versus the coloniser

“Along the new Silk Road”’ also features various human interest stories. Brandt Corstius, for example, interviews a Kyrgyz woman about the declining popularity of the Russian language in her country and the revival of nomadic traditions.

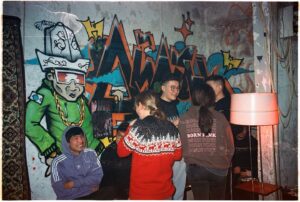

In Pavlodar, Brandt Corstius’ ends up in a hipster bar to talk with progressive Kazakh youth about the sudden influx of Russian draft evaders. These stories definitely deserve praise, as they help empower local narratives about the quest for (national) identity.

But too often, the documentary makers frame these storylines to fit within their geopolitical grand scheme of things. A clear example of this is Terlou’s poignant interview with several Kazakh women who were imprisoned in China’s internment camps in Xinjiang, or had family members taken from them.

Read more on Novastan: Escape from Xinjiang – stories from those who fled the camps

One by one, these women’s accounts are chilling. It is impossible not to be moved by their stories of torture and forced abortion. But after the conversation has come to an emotional climax, the camera pans to Terlou who is sobbing quietly in a corner of the kitchen. Later, in a phone call with Brandt Corstius, Terlou describes that hearing the stories of the Kazakh women felt “as if going through a break-up” with his beloved China.

Decolonising a documentary

It is commendable that Dutch public broadcasting was willing to fund this documentary. After all, the show helped introduce hundreds of thousands of people to Central Asia, many of whom had never heard about the region before.

Yet, in “Along the new Silk Road”, Central Asia appears to be little more than an endless procession of postcolonial pain and misery. Although decisions made in Moscow and Beijing still resonate in Central Asia, regional political leadership has far more agency over the geopolitical course of their respective countries than the documentary portrays. And more importantly, the people in the region have their own histories, cultures and ideas about the future.

Only when Western media acknowledge these unique identities, it is possible to move away from lingering orientalist views of Central Asia and – hopefully – start making documentaries the region deserves.

Written by Julian Postulart

For more news and analysis from Central Asia, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Telegram, Linkedin or Instagram.

Orientalism revisited – a very Dutch introduction to Central Asia

Orientalism revisited – a very Dutch introduction to Central Asia

Jacques, 2025-03-11

Just ran into your article because some of our Russian friends sent us pictures of them having a vacation in Kyrgystan. My question to you would be: are you a native speaker of the Dutch language? The two guys that made the documentary series and also their employer VPRO are the opposite of orientalists. You may have missed a lot of nuances in their documentaries.

Reply

Julian, 2025-08-23

Hi Jacques, thanks for your comment. I’m a Dutch native, so no problems there. I know the two presenters have made some great documentaries in the past, but with this one they missed the mark – and included quite some cliches about the region. Even a renowned public broadcaster such as VPRO can fall into the trap of orientalism. Framing Central Asia as a mere subject to a power struggle between Russia and China reduces local agency and regional nuances, leaving little space for Central Asian narratives.

Reply