“All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others” is one of the most famous mottos in world literature. The novel it comes from, George Orwell’s Animal Farm, is now available in Kyrgyz. Novastan met with the pair behind this new translation.

For readers in Kyrgyzstan, George Orwell’s Animal Farm has historically only been available in Russian. Anthropology student Ilyas Kanybek and his grandfather, the political scientist Aalybek Akunov, decided to change that by translating the novel into Kyrgyz.

Want more Central Asia in your inbox? Subscribe to our newsletter here.

Kanybek and Akunov were motivated by their belief that philosophical texts have a fundamental role to play in society. They promote critical thinking, transmit cultural heritage and address fundamental questions. Nevertheless, many Western philosophers or main figures of world philosophy have not been translated into Kyrgyz. It is also the case with George Orwell. They thus see their translation as allowing Kyrgyz readers to access this popular and fundamental philosophical novels.

A way to “understand totalitarian mechanisms”

“The main motivation for translating Orwell was the simplicity of the allegory, as well as the simple and accessible writing style of Animal Farm, which are able to describe what people experienced during Soviet times,” Aalybek Akunov explains. “Nowadays, I can hear people saying with idealized nostalgia that ‘it was better before’. My answer is categorical: ‘no, it is not!’

“Look at the statue of Iskhak Razzakov [first secretary of Communist Party of Kirghizia] in front of our Politech University, which replaced the statue of Lenin, the latter moved and hidden behind a tree hedge,” he adds. “What does it change? Razzakov is Kyrgyz, of course, but he was a communist! And communism is international. It doesn’t matter whether you are of a particular nationality. I hope that this translation will enable people to understand the totalitarian mechanisms that we experienced during 70 years of Sovietism, which inertia have been working on until today.”

Ilyas Kanybek, two generations younger, approaches translation in a different way: “As for me, this book shows how individuals, faced with such an event, choose their path. I consider this book as Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave”. People need to read and start asking questions and wondering about the society they live in,” he explains.

“But my motivations and my grandfather’s are the same: everything was not crystal clear in Soviet times and I think Animal Farm can really help us to open our eyes, and investigate a period which is still murky and subject to various interpretations or misunderstandings. I find it regrettable that people praise such Soviet old times, but I assume we need to put that behind us and deal with more concrete issues, to be focused on the present and the future.”

Connections to Kyrgyz culture

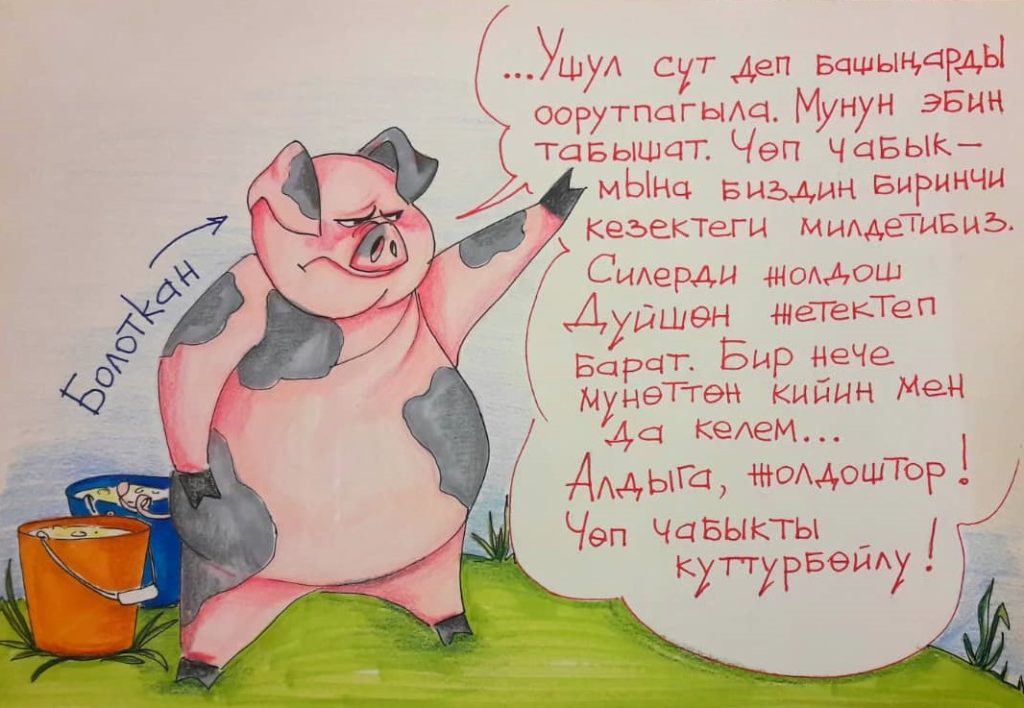

Translation is also an adaptation process which bridges different cultures through language. For example, the translators made the choice to change some character names.“Some characters’ names have been changed so that the Kyrgyz reader can make connections with his own culture,” Akunov clarifies. “For instance, the main character, Napoleon in the original, imposes himself as the supreme leader through his tyranny and his authoritarian control. This character clearly designates Stalin. Thus, in Kyrgyz, he was given the name Bolotkan. It’s merely a transposition of Stalin (‘Man of steel’) into Kyrgyz, ‘bolot’ denoting ‘steel’ and ‘kan’ the one who has the power.”

This technique was not applied to all characters. The translators also decided to rely on the Kyrgyz poet Chyngyz Aitmatov’s works in borrowing character’s names. “Indeed,” continues Akunov, “the main opponent of Napoleon is Snowball who, in our translation, was named Dyuyshen (Duishon). For the Kyrgyz reader, Dyuyshen is the main hero of Aitmatov’s novel, The First Teacher. I chose this name because Dyuyshen is an enlightened communist, who really wants to improve the society, and to introduce changes. Another example is Old Major, the one who envisions and foresees the Revolution, has been adapted into Kartan Lenbay, that is to say, ‘the Lenin-like Old Timer’.”

Read more: Kyrgyzstan: threat of censorship looms after controversial comedy show

They chose Aitmatov because of his status in Kyrgyz literature. “Aitmatov is a well-known writer, not only famous in Kyrgyzstan but also abroad,” Akunov points out. “His characters are known to all, they carry an inherent symbolism which is common for every Kyrgyz. As such, Aitmatov’s œuvre represents a well from which we can draw several references. Our choices are, of course, guided by the temperament and the behaviors of every characters. Thus, Benjamin, the donkey, was nicknamed Orozkul, a direct reference to this personage from The White Ship.

“Even if Benjamin is not that violent, both characters share and bear this pessimistic vision of life, and use to adopt the new values (Animalism for the latter, Sovietism for the former) without reject. I used also the name Bazarbay to portray Mr. Whymper. Bazarbay is a character from Plakha and means ‘the one who is negociating’.”

The same idea was applied to rename Boxer, Animal Farm’s hard-working horse character, into “Tanabay”, a name from Aimatov’s most famous novel, Farewell Gulsary. “Boxer is a kind of Stakhanovist, doing what he was asked and even more. This is exactly the main features of Tanabay,” Akunov explains. When asked why they didn’t choose “Gulsary”, the name of a horse in the same novel, Akunov says: “It would have been more logical to call him Gulsary as we are dealing with a horse, but Gulsary is, in Kyrgyzstan, a character associated with positive values, which is not the case of Tanabay, his master.”

An accessible language

For the pair, translation is also a way to reject the idea that there is no need to publish a text in Kyrgyz if it is already available in Russian, something Kanybek says comes from the “tenacious cliché” that people in Kyrgyzstan speak Russian more than Kyrgyz. “By translating Orwell into Kyrgyz, we can give it to read to a larger population, to a population who has not a good command of Russian, an essentially Kyrgyz-speaking population,” he explains. “In Kyrgyzstan there are a number of dialects but which are unified in Kyrgyz literature into a single standard language, accessible to all.“

In addition, Kanybek says, this literary language has all the necessary vocabulary to translate Orwell: “We had no issues finding an equivalent in Kyrgyz for some specific idioms and terms. The Kyrgyz language was integrated into the modernization process during the Soviet era, and – this is a positive consequence – broadly developed its vocabulary to fit modernization.”

Alamanova

But Akunov is not very positive about Kyrgyzstan’s literary production. “We can identify two kinds of Kyrgyz literature,” he comments. “One is Kyrgyz literature, by local writers, which I do not esteem as it does not address global issues, and stays naïve. On the other hand, we can witness an increasing production of the literature translated into Kyrgyz, recently with Herman Hesse for example.”

Translating Animal Farm took Kanybek and Akunov several months, from December 2019 to February 2020. They looked not only at the English original but also at existing translations into Russian and other languages. Kanybek singles out Polish, the first language Animal Farm was translated into. “We wanted to observe and analyze how the different translations succeeded in contextualizing the novel, and to understand the possible mistakes made compared to the original,” he explains.

The pair are publishing and distributing their work themselves. “We have not signed yet any agreement with local bookshops,” Akynov says. “We gave several conferences and presentations to speak about our work, and to sell it. For the moment, we are selling thanks to an effective word of mouth.”

“We also decided to fix the price up to 200 soms [around £1.7],” Kanybek continues, “which is a normal and affordable price for a new book here. We published it at our expenses and depending on the success of the first print run (2000 copies), we’ll do another one.”

Both translators insist it is a collective work:“We would like to note that the translation was a big part of the job, but the book would have been uncompleted without the generous help of our illustrator, Cholpon Alamanova, who drew original pictures for it.”

But they don’t want to stop here and already have new translation projects in mind: next, Akynov says, he would like to translate Bulgakov’s Heart of a Dog into Kyrgyz.

Julien Bruley

All illustrations courtesy of Cholpon Alamanova

For more news and analysis from Central Asia, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Telegram, Linkedin or Instagram.

“Ayban Ferma”: translating George Orwell into Kyrgyz

“Ayban Ferma”: translating George Orwell into Kyrgyz