ANALYSIS. Last spring, a violent crime against a young woman in Uzbekistan moved the general public. It was followed by a unique feminist protest on social media. For the Uzbek blogger Nadira Khalikova, this incident is representative of the type of views that perpetuate the oppression of women in Uzbekistan.

This article was originally published on Novastan’s German website on 15 September 2020. Please note it contains descriptions of physical and verbal violence against women.

When a woman learned to read, the woman question arose in the world

(Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach)

A 17-year-old woman and her friend are walking their dog in the park in Farg’ona (Fergana), western Uzbekistan. The young woman is wearing shorts and a top. She is approached by a man in the park, who whistles at her. After the young woman ignores him, he insults her, saying: “All Russian women are sluts.” She does not react and keeps on walking with her friend. An hour later the man returns with 30-40 other men. He talks to her again and she tells him to leave. The young man, a 21-year-old named Nodir K, pulls her by the hair and beats her.

The woman, Evelina, is taken to the hospital that same day, 31 May 2020: her jaw is broken in two places, and for two weeks she can only eat through a feeding tube. The incident was reported by local media such as the online publication Podrobno.uz. A criminal case for assault and battery was only opened arond two weeks later, on 16 June.

Want more Central Asia in your inbox? Subscribe to our newsletter here.

However, after a couple of days, Evelina and Nodir came to an agreement and the case was dropped. The young man publicly apologised and covered all treatment costs. “I hope that there will be no more mentions online ofthe incident. It is unpleasant both for me and her,” Nodir declared, as reported by the Russian media Fergana News.

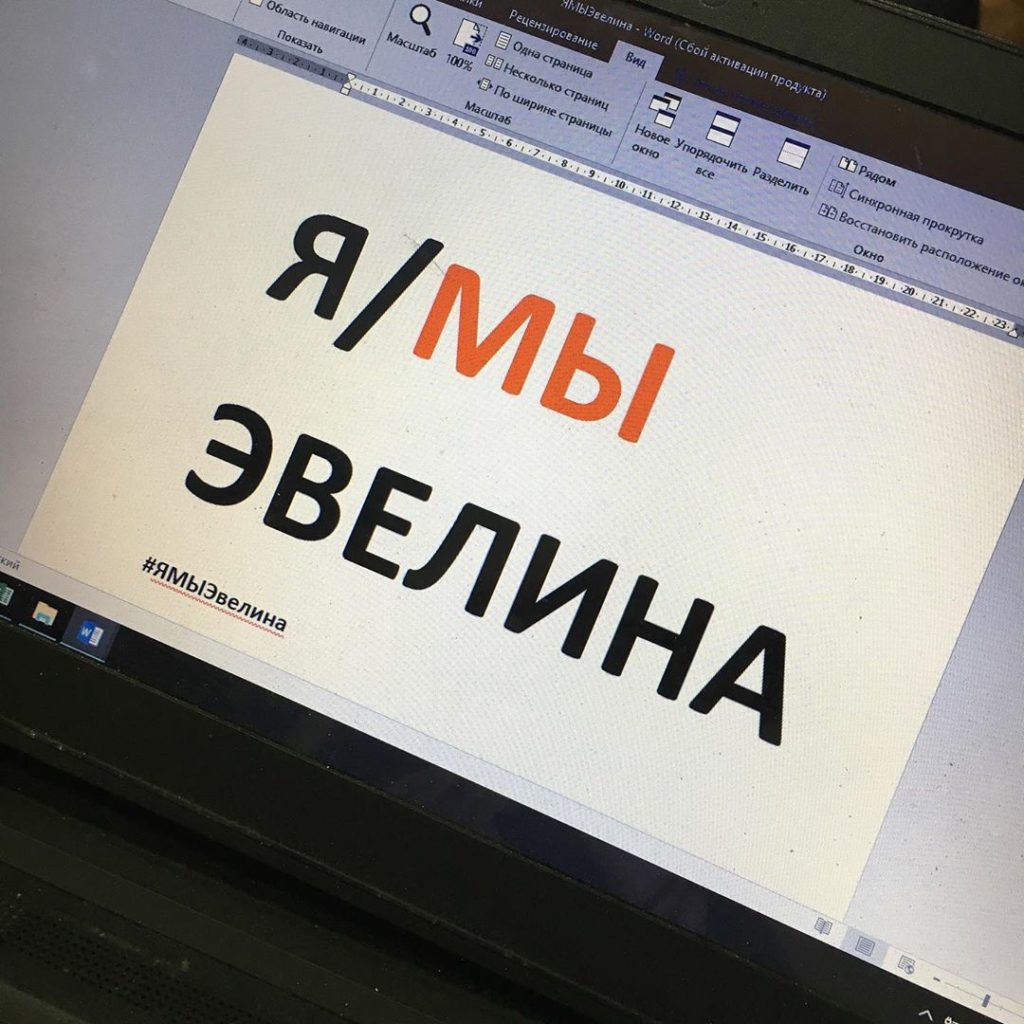

Nodir’s statement, in particular, triggered public reaction and resulted in what is believed to be one of the largest feminist protests in Uzbekistan in recent years. The hashtag #yamyevelina (#ямыэвелина, “I am / we are Evelina” in Russian) was used on social media in solidarity with Evelina. With this hashtag, many women told their own experiences of violence through pictures, illustrations and videos. #jamyewelina seemed to be the Uzbek #metoo.

As a result, on 6 July, a “flashmob” against sexism and discrimination against women took place online. Cardboard signs read: “Russian woman does not mean slut”, or “Kelin (daughter-in-law) does not mean slave”, “Whoever hits goes to jail”, “My body, my business”. These slogans echo well-established expressions that promote the oppression of women. Such phrases are common: for example, “he beats you up, so he loves you” or “the kelin has to do all the household chores alone”.

While the subject has been highly discussed online, the authorities remained silent. Especially two institutions: the Gender Commission (which should not tolerate such treatment of women in society) and the recently founded ministry for supporting mahalla and family.

A typical case

Nodir’s actions, however, require specific analysis. To put it simply, the following happened: a man tried to hit on a woman who, in his opinion, was dressed “indecently”. She does not react and he brutally assaults her. They find an agreement, resulting in him not being convicted.

There are many hypotheses as to why Evelina agreed to drop charges. One can in this case spot patterns that reveal a lot about the role of women in Uzbek society and the nature of relations between men and women: blaming the victim, the Uzbek concept of ma’naviyat as a means of social oppression and, lastly, the idea that women have to accept their lot regardless of the difficulties they are facing.

Victim blaming is in Uzbekistan, as in many other countries, a widespread phenomenon: women are considered “sama vinovata”, that is, “they have only themselves to blame” when assaults occur if they have not “behaved with dignity”. They are held responsible if something happens to them, especially a woman who is not “decently dressed”. This is considered a sort of invitation to harassment. “If women don’t want us, men, to approach them and hit on them, then they have to dress decently. If I see a woman dressed in short clothes or showing a lot of skin, I assume she wants a man to approach her. I would never hit on a decently dressed woman,” said Anwar (his name has been changed), an engineer from Bukhara, for example. Such behaviour is further justified and explained by ma’naviyat.

Ma’naviyat is a very important word in modern Uzbekistan, meaning virtuous, orderly, perfect. One has to be worthy to achieve ma’naviyat. Ma’naviyat is taught in multiple ways, from primary school to university. The concept sometimes includes a certain idea of what a “decent” woman should be like. According to this ideal, for example, she does not wear jeans, she wears “reasonable” make-up, she is very well-behaved and sweet. She does not contradict anyone. She does everything that first her parents and later her husband tell her to do. And of course she has never been in a relationship and is still a virgin when she marries. She does that at the age of 22 at the latest and gives birth to two-three children, whom she raises as “worthy”, or ma’naviyat, people. She can cook and bake well and will thus make her husband, his family and her children happy and honour them.

Media criticism of the feminist protest

At the end of August, during the programme Munosabat (a word meaning opinion, relationship to a subject), the state TV channel O’zbekiston addressed the #jamyevelina movement. The participants of the programme strongly criticised the 6 July flashmob. Jamila Shermuhamedova, a former staff member of the Committee for Women’s Rights, was particularly critical: “Yes we passed a law on gender equality … But the law does not say: ‘I will do what I want, I will walk around naked, I will not marry, I will not give birth, I am not a servant’ … you have to bow to national values because there are laws and a constitution.”

Thus, national television shows pure propaganda that minimises any attempts by women to demand their rights. The flashmob also received abusive comments on social media, especially from men. For example, the football commentator and journalist Bobur Fozilxon wrote on his Facebook page: “Why are you paying much attention to the few f****-up tampons walking around with cardboard signs? Just ignore them.”

As can be seen, women who stand up for gender equality are stigmatised as “sluts”. Society only celebrates one type of woman: a woman who does not disagree. A woman who conforms to the “ma’naviyat”. A woman who, despite all obstacles (especially if she is already married), endures in silence and teaches her daughters to do the same. In Uzbekistan, women have elevated forbearance to a particular philosophy. It is ultimately one of the few ways to survive as a woman.

It is questionable whether Evelina’s case and the #jamyevelina flash mob will change anything in the short term. But they are among the first, conscious and “loud” actions led by Uzbek women to demand their rights and to fight for free speech. The events have made the idea of a strong and independent woman trendy, especially among younger people. It is starting to be cool to have a voice as a woman and to fight for that voice. That is how the question of women’s rights has come to Uzbekistan.

There are strong women in Uzbekistan. They could contribute more to building the future of the country if traditions, ma’naviyat, gender inequality and, ultimately, their whole upbringing did not limit them to daily household chores, in-laws and husbands.

Nadira Khalikova

Translated from German by Manon Montant

For more news and analysis from Central Asia, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Telegram, Linkedin or Instagram.

Uzbekistan: when women demand to have a voice

Uzbekistan: when women demand to have a voice