The situation of queer people in Kyrgyzstan has worsened in recent years. Repressive laws and negative portrayals in the media are putting the community under increasing pressure. At the same time, there are still niches in which queer life can flourish.

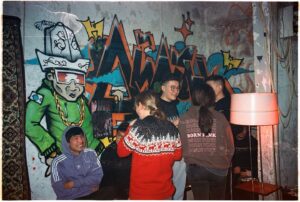

The more homophobic and hostile towards queer people a society is, the more important it is to have safe spaces where LGBTQ people can be themselves. The only gay bar in Kyrgyzstan is one of these safe spaces. You won’t find it on Google, only insiders know where the “G.” bar is located. For eight years now, the bar in Bishkek, which is actually more of a night club, has been offering a safe space not only for members of the queer community, but also for women regardless of their sexual orientation. The large dance floor and cheap drinks are popular with young people, with up to 600 guests coming at the weekend, says Zhenya, the owner of the bar. It’s quieter during the week, but the bar is open every day, because you can always use a safe space: “People want to go somewhere. Not everywhere it is safe to show your affection to your partner or flirt with someone. So, they come to us.”

The bar is named after the G-spot: “A place where it feels good, but it’s not easy to find,” says Zhenya with a laugh. The fact that the address of “G.” is not publicly known and there is no sign on the door has to do with security. In spite of security measures, stones have been thrown at the bar, a neighbour has attacked guests and passers-by have called the police when they realised they had stumbled upon a gay bar. “The police have been causing us stress since day one,” says Zhenya, but the bar has not been seriously threatened.

In addition to “G.”, there are other safe spaces, such as the community centres of the LGBTQ organizations Kyrgyz Indigo and Labrys, where various events take place, from English-speaking clubs and craft workshops to information evenings on health issues. And safe spaces don’t have to be physical spaces, they can also be found on the Internet, for example the online medium “QueerQyz”. The activists Artur and Akbermet produce funny and informative videos in which queer people talk about their lives. “We have only a few media with queer representation in Central Asia. We think it’s important to show that there are many queer people in Kyrgyzstan,” says Artur. QueerQyz is a medium by queer people for queer people. Its aim is not to explain things to hetero-cis people, but to give queer people the opportunity to find themselves represented, to realise that others have similar experiences to their own.

Rejection and violence: homophobia in society

In Kyrgyzstan, many queer people keep their identity a secret in order to protect themselves from violence and discrimination. Filming and taking pictures are therefore prohibited in the “G.” bar. This is because outings – the involuntary disclosure of a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity – can have serious consequences; from rejection by one’s own family and bullying by colleagues and classmates to job loss and physical violence.

“My family doesn’t accept me. I live with my girlfriend’s family. They accept us as a couple. Our freedom ends at her house. We can’t be a couple anywhere else. Not at work, not among friends.” This is how a study by the NGO Labrys quotes a lesbian woman from the Chui oblast. Another woman expresses a similar view: “I’m really tired of hiding. My girlfriend and I have been together for seven years. We’re only together in our bedroom. In all other places, we’re not together. On the street, we’re not together. We can’t go out together.”

Visibly queer people report being harassed on the street with inappropriate questions, such as why they paint their nails or look like a girl. In conservative families, there are often attempts to “cure” queer family members by means of psychiatrists or religious authorities.

Read more on Novastan: LGBTQIA Muslims – “An online imam with background music is hardly the absolute truth”

But there are also parents who accept and support their children. There even is a parents’ group that meets regularly in Bishkek and talks about their experiences as parents of queer children. In general, the situation for queer people in Bishkek is much better than in the regions. In the capital, there is better access to information and support, there are safe spaces and it is more likely to meet open and non-homophobic people than in villages. In more rural regions and smaller towns there are hardly any opportunities to come together as a community. “We don’t communicate with each other, it’s dangerous. Of course, we want to communicate, but the risk of being outed is too high, so we hide in small groups,” says a participant in the Labrys study who lives in Osh.

If a person’s sexual orientation becomes known, there is a high risk that they will experience violence, threats, and blackmail. A study by the organization ECOM documents several cases in which members of the state authorities lured queer people to fake dates and then extorted money from them by threatening to out the person in front of their family.

Most of the time, LGBTQ people who experience violence and discrimination do not press charges as they cannot expect any help from the authorities. At police stations, they are mocked and threatened, if not the police officers themselves were the attackers in the first place.

Exclusion from public life: the marginalization of trans people

Alongside HIV-positive people, trans people are among the most marginalised members of the Kyrgyz LGBTQ community. The risk of experiencing violence is particularly high for them, and ridicule and rejection are everyday experiences. In addition, there is no access to high-quality hormone preparations in Kyrgyzstan and as most trans women are involved in sex work, the working hours of the few available endocrinologists don’t fit their schedule. This means that many trans women do not have access to tests and examinations. Since a change in the law in 2020, it is also no longer possible to change the gender marker in official documents.

Situations in which ID must be presented are particularly tricky for trans people. Often, problems arise when the person’s appearance is not recognised as matching the stated gender. Many trans people therefore avoid going to the doctor, reporting criminal offences or even opening a bank account, as Anelya, coordinator of the MyrzAiym initiative, which supports trans people in Kyrgyzstan, reports. Anelya talks about her own experience with doctors: “Three or four years ago, I ended up in hospital. I had to have emergency surgery. The doctor who was supposed to operate on me came to me, saw me, saw my papers and said: I don’t operate on people like that.” It was only with great difficulty that a former colleague who had accompanied Anelya to the hospital was able to find a young doctor who was willing to perform the operation. Trans people cannot rely on receiving medical care. That is why many resort to self-medication.

There are also hardly any opportunities for trans people to pursue a regular job or gain access to higher education. In a study by the organisation Kyrgyz Indigo, a trans woman says: “I wanted to go to medical school, but because of my gender marker they don’t allow me to study. I applied to study in 2021, but was not accepted.”

Public life remains closed to many trans people and fear is a daily experience. Another study quotes a trans woman from Bishkek: “I’m afraid to open my mouth in the street. Because there’s a man’s voice. I stand there like a mute. Because if I speak, it’s clear I’m trans. What would happen then, you can imagine. That’s why I always keep quiet in the street. It is especially frustrating when people come up to ask me something, I want to help, but I leave like a frozen person, because I am afraid that they will realise that I am trans.”

This makes safe spaces for trans people and mutual support within the community all the more important. Anelya has therefore set up a WhatsApp group where people can get in touch if they need help. The MyrzAiym initiative also regularly offers leisure activities such as volleyball or swimming in a safe environment to enable trans people to pursue hobbies that they cannot do in public, for example because they cannot show themselves in a swimming costume or in the changing room at the sports club.

The battle for “traditional values”: queer people as scapegoats

While the acceptance of queer people in Kyrgyz society has never been particularly high, their situation has deteriorated further since the beginning of Sadyr Zhaparov’s presidency in 2020. Zhaparov, who is in the process of transforming the country into an authoritarian state through numerous legislative changes, is pushing the narrative of Kyrgyzstan’s “traditional values” and placing questions of morality and national identity at the centre of his campaigns. Similar to state propaganda in Russia, in recent years the Kyrgyz mainstream media has frequently referred to a corrosive Western influence. Homosexuality is said to be a Western “import” that is destabilizing the country and its values.

During the 2020 election campaign, a secretly recorded video showing two men having sex was circulated on social media to discredit an opposition party. “These Kyrgyz people were not affiliated with a political party at all, but hoping for a homophobic reaction, Kyrgyz political technologists used their lives to promote someone else’s political interests,” reports the independent medium Kloop. However, such critical reports in the Kyrgyz media are rare. After monitoring the media between October 2022 and June 2023, the NGO Kyrgyz Indigo came to the following conclusion: “We analysed more than 200 stories that highlighted the queer community. Almost 80 per cent of the news items were stories that said that the existence of LGBT+ people leads to the destruction of national identity, morality and family values.” In the news items, NGOs that receive funding from abroad were also discredited. Many articles argued that they served Western interests and worked towards weakening traditional Kyrgyz values.

Queer tradition: a counter-narrative

LGBTQ activists are striving to counter the claims that homosexuality and queerness are at odds with Kyrgyz identity and tradition by showing that queerness has always been part of Kyrgyz history and can also be found in folklore and traditions. For example, the name of the medium QueerQyz refers to the historical name of Kyrgyzstan, which is composed from the words “kyrk” (forty) and “qyz” (girl). “There is a legend that tells that our nation was created by 40 girls, which is a little bit queer,” says Akbermet, one of the founders of QueerQyz.

However, such attempts to associate tradition and folklore with queerness provoke particularly negative reactions from conservative citizens. Akbermet talks about illustrations she created for QueerQyz’s Instagram page: “I drew our yurt with a rainbow coming from it and two girls that are kissing who are wearing our national clothes, which of course, caused a lot of hate.” There were many hate comments under the post, reproducing the propaganda narrative spread by the government and mainstream media. “Please don’t use national themes. Our people are not so depraved when it comes to this [homosexuality]. It’s fine in Europe, but it’s not welcome in our country,” reads one of the comments, with many others sounding very similar.

“LGBT propaganda” and “foreign agents”: Laws based on the Russian model

It is clear that the anti-queer propaganda is falling on fertile ground with many citizens. The government is also using the anti-queer sentiment to introduce restrictive laws. Since August 2023, it has been illegal to disseminate material among minors that denies traditional and family values and advocates “non-traditional sexual relationships”. The law is very similar to the Russian law of 2013, which also banned so-called “homosexual propaganda” among minors (recently this law has been replaced by a more restrictive one that bans all queer content in Russia). However, the Kyrgyz law is less clearly formulated than the Russian one, so that it is not clear in which cases the law is broken and in which not. In Russia it was for example possible to distribute queer content with “18+” warning labels. It is unclear whether such warning labels are enough to protect against prosecution in Kyrgyzstan. Such vaguely formulated laws are a license for repression, as they can be interpreted by the authorities and courts at will.

Queer organizations and media are dealing with the new law in different ways. Some are barely posting on social media anymore and are no longer organizing events, while others are continuing to invite people to events and publish information – albeit with “18+” warnings.

Read more on Novastan: Uzbekistan – pro-LGBTQ blogger victim of violent attack

For NGOs working for the rights of LGBTQ people, it is also generally unclear whether and how they can continue their work. In October, a draft law was passed in first reading by the parliament that is very similar to the Russian law on “foreign agents” and is aimed at NGOs that receive funding from abroad. LGBTQ organizations could not exist in Kyrgyzstan without money from abroad. If the text is signed into law, the affected NGOs will have to register as “foreign agents” and be subject to strict controls. Also, a new article is to be added to the penal code. It states that if someone founds or co-operates with an NGO that “violates the personality or rights of citizens”, they could face up to ten years in prison. What exactly it means to violate the “personality or rights of citizens” is not defined. So, the law can be used against unwelcome activists, who are already frequently exposed to the risk of attacks and outings.

The restrictive laws and anti-queer narratives in the pro-government media also mean that homophobic citizens feel confirmed in their resentment and see themselves as being on the right side when they attack queer people. “People feel safe that they can harm queer people. They just do it because they know the government won’t protect us,” says Akbermet, who herself was threatened and outed in front of her family.”

“Dark times”: defending the status quo

One activist from the organization Labrys speaks of “dark times” in light of these developments. There is a prevailing feeling of uncertainty in the queer community, as they don’t know what will happen next, what they can and cannot get away with. This lack of clarity is gruelling, says “G.”-Bar operator Zhenya: “As far as the draft laws are concerned, are we feeling their effects? Not yet. But it is very likely that we will feel them. I don’t know if it will affect us at all. But all the time we live in fear, what will be affected?” The medium QueerQyz has made their content invisible on Instagram until it is clear how exactly the law works.

Activist Meena (pseudonym) from Kyrgyz Indigo adds: “We are all very exhausted. We can’t even imagine, what is awaiting us and we can’t even guess, what can happen. We just move like we used to, try to live our normal life. But in the background, we understand that it’s not how it used to be. We don’t know how to act in the new realities. So, it stresses us out.”

Many activists seem to agree that it is not the time to be loud and fight for more visibility, but to protect the community and defend what has already been achieved. “I think right now what we have to do is to keep safe. Our goal is to keep what has already been done, because a lot of work has been done. I personally think that it’s not the time for growth. Maybe just to protect,” says Meena, but then adds: “But historically crises are the best time for breakthrough.”

Hope and resilience: carrying on despite an uncertain future

The queer community in Kyrgyzstan has achieved a lot in recent years. They have actively advocated for their rights and organised successful campaigns that have increased awareness of anti-discrimination issues. Safe spaces and active networks have been created, and queer people can find medical, legal and psychological help in several NGOs. LGBTQ artists and activists have successfully appropriated and reinterpreted symbols and narratives that many conservative, queer-hostile and nationalist citizens claim as their own.

Time and again, the community has proven its strength and resilience under adverse circumstances and demonstrated its determination to defend what it has achieved and carry on despite everything. And so, despite the difficult situation, queer life in Kyrgyzstan continues: at the end of October, a big queer Halloween party was celebrated in the centre of Bishkek with a drag show and vogueing on stage, and in November, the Fem Museum initiative opened a large exhibition of queer art.

All of this is still possible. Whether it will stay that way and what the future holds in Kyrgyzstan is uncertain. There are few reasons for optimism, but the community seems determined to continue to make use of the freedom that is still available and to fight to ensure that the situation does not deteriorate any further. “In a situation like this, it’s very difficult not to lose hope,” says Artur from QueerQyz. “But I always have hope.”

Written by Norma Schneider

For more news and analysis from Central Asia, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Telegram, Linkedin or Instagram.

Queer life under pressure in Kyrgyzstan

Queer life under pressure in Kyrgyzstan