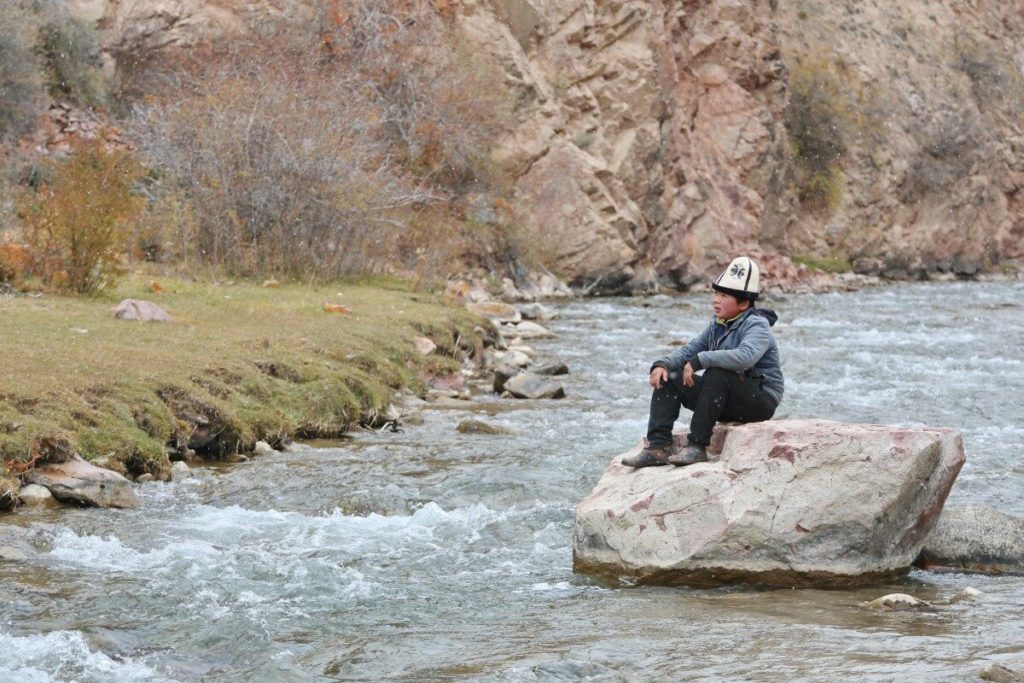

LIFE BY THE RIVER. As a source of water and energy, the Naryn is one of the most important rivers in Central Asia. The effects of climate change are evident, especially downstream, which could have dire consequences for the entire region.

This article was originally published in Russian by the Kazakh media Vlast.kz as part of the “Developing Journalism: Exposing Climate Change” project. For this report, journalists interviewed residents along the river about their relationship with the Naryn.

The Naryn River starts its journey high in the Tian Shan Mountains in Kyrgyzstan. In the Fergana Valley, the Kara Darya River flows into the Naryn, starting the Syr Darya River, one of the main waterways of Central Asia. Three provinces of Kyrgyzstan, one province of Tajikistan, six provinces of Uzbekistan and two provinces of Kazakhstan lie in the Syr Darya basin. The river connects four of Central Asia’s countries.

Want more Central Asia in your inbox? Subscribe to our newsletter here.

According to Ismail Dairov, director of the Central Asia Regional Mountain Centre in Kyrgyzstan, “water flow from the Tian Shan and Pamir Mountains along the Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers could decrease by 10 to 30% in the next ten to twenty years”. Scientists and experts point to the region’s fast-growing population, which demands more and more water.

As part of the “Small People – Big River” project, a group of journalists and environmentalists travelled along the Naryn River to ask people who live near it what changes they see in the river’s behaviour or the weather. And how it is changing their lives.

“The owner is he who looks after the land”

Originally from the Transbaikal in Russia, Sergey Zolotuyev came to the area 53 years ago and decided to not go anywhere else. He repeats a well-known proverb: “Everywhere is good where we are not”, a Russian equivalent to “the grass is always greener”.

“This place is a source of health, and what else does a man need? Here I live surrounded by beautiful mountains, beautiful vegetation and a mountain river, clear as ice. Every plant here is medicinal. There are no factories or plants above us, I want to breathe in the air with all my heart. This nature makes me feel positive, and my friends too. At 57, I jump around on the rocks every morning, I keep my weight, not a gram too much,” Zolotuyev says.

“When people from city apartments visit me and breathe the uncontaminated air here, they go back literally refreshed. All their negativity is collected by the water and upon their return home, nature beckons them back. That is why foreigners fall in love with our nature too”, he adds.

“I have found that by living among such nature, one becomes sensitive and attentive to everything around. Here I notice every blade of grass, how the hawthorn becomes blood-red, how the barberry turns red and darkens. How ants, magpies, crows live. And how the climate is changing and degrading our ecosystem.

We cannot influence the climate globally, but at local level, yes, without a doubt. For example, it is in our power to develop the economy. There is no irrigation or arable land, Kyrgyzstani people live mainly off cattle, increasing their number, but they are not engaged in selective breeding. These huge cattle herds disturb the vulnerable fertile soil layer. The grass is low now, not what it used to be! There haven’t been blackberries in the swamps for a long time. Cattle eat them and leave behind only miserly small bushes,” Zolotuyev says.

Read more: Talas and its people: life by a Central Asian river affected by climate change

He concludes: “It is also in mankind’s power to not litter, but in every gorge there is trash. The only thing that surrounds us is trash. It gets into the water. And it is carried to those who live downstream. At Issyk Kul lake absolutely everything is covered in garbage. I go and collect the trash but I don’t complain- it is my contribution to protecting nature. About that I want to say: The owner is not he who measured the territory, but he who looks after it! He who loves and respects his land. He who thinks of the others living downstream. I want the people downstream to have clean water. As those upstream do.”

A river full of trash

Musa Borbiev, a trout fisherman from Toktogul, in central Kyrgyzstan, agrees. He urges to protect the river.

“People throw food leftovers and plastic into the river, the fish die from all that trash! Trout love clean river water, so they are becoming fewer. The most important thing is uncontrolled fishing, nobody protects it. Careless fishermen catch 100-150 fish at a time, they violate the balance. They clearly do not fish for their own consumption, but for sales. That is why they fish with electric rods and with nets. And thus the fish become fewer, and they are not regenerating”, he says.

Musa is 57 years old and has lived in this area all his life. He points out that in his lifetime, the climate has changed significantly. “Before people could walk on the ice in winter without a worry, since it was up to 40cm thick. Now it is not like that. And there is no snow, like there was in my childhood. The level of water in the river is decreasing”, Borbiev says.

A few years ago the fisherman started breeding trout in artificial ponds. Buyers from Osh and Jalal-Abat, two cities in the south, as well as local inhabitants buy ecologically friendly fish from him. He laments that it has become harder to buy fodder: it comes from Europe and the price varies according to the fluctuations of the Kyrgyz currency, the som. Sometimes, he buys fodder in Kazakhstan, but that is only a little cheaper and significantly worse in quality.

Borbiev would like to produce feed for fish himself, but many of the necessary ingredients are not available in Kyrgyzstan, such as fish oil and fishmeal.

Valentina Lukina from Tashkömür, a town a little further downstream, is a journalist and commended teacher of the local technical school. She also speaks of the deteriorating state of the Naryn river.

She explains: “Not only do polluted tributary waters flow in here, but people are even transforming the Naryn itself into a sewer. The Naryn river, in fact, functions as a deposit for the waste products of human activities. The city hospital, which dumps its medical waste in the water, and badly functioning wastewater treatment plants, contaminate the water. And we are not protected against sick animals. Do you have an infection? That’s not an issue. Yes, people live along the river and they need precisely this water to meet their basic needs. That is the water cycle”

According to official figures, in the past 50 years 40 million cubic metres of sewage water drained into the Naryn river.

Valentina Lukina was born in Tashkent but came to Tashkömür when she was three years old, when her parents came to work at the local hydropower plant. According to her observations, changes in the intensity and frequency of the winds and the decrease in the water levels are signs of climate change, even though the river remains full of water and powerful.

“The river is a source of life”

Ulan Namatbekov is a gamekeeper from Naryn city, where he was born, grew up and has lived his whole life. He also speaks about how the largest water artery of Kyrgyzstan could become the cause of a transborder ecological catastrophe. Sewage, trash and industrial waste have already flown down this river for a long time.

The wastewater treatment plant of the city of Naryn is over 50 years old. At the time of its construction the population was not large, but now the plant’s capacity does not meet the city’s needs. Sewage is not cleaned biochemically, it is simply drained into the Naryn after mechanical treatment. People living downstream then use it for cleaning and irrigation of their fields. They have no other choice.

Namatbekov worked for a long time as a researcher in the Naryn State Reserve, which is located upstream. In the western part of the reserve there is a separate nursery for breeding red deer.

Namatbelov is an eco-activist and convinced that Kyrgyzstan needs ecological education. He has initiated public hearings in Naryn with the participation of local administration and eco-activists about the problems connected to human activity and climate change.

Read more: Kazakhstan: replenishing the Aral Sea’s fish stocks

The ecologist notes the gradual decrease of glaciers, which are the sources of the Naryn river. He says: “This is the longest river in Kyrgyzstan and an inflow of the Aral Sea. The countries around the Aral Sea did not use the water correctly and the Sea dried up. Let’s not repeat that catastrophe and let the glaciers melt.”

According to Sulton Rakhimzod, chairman of the executive committee of the International Fund to Save the Aral Sea, the total area of glaciers in Central Asia has already been reduced to a third of what it was at the beginning of last century. With a two degree rise in temperature the glaciers will shrink by 50%. If the temperature rises by four degrees, the glaciers would lose up to 80% of their mass.

“The Naryn river is a source of life,” says Oleg Nekrytov, head physician of the Central Hospital in Ming-Kush, a town in the Naryn region and a former uranium mining site.

Nekrytov was born here in 1963 and did not leave when many Soviet uranium mining settlements started shutting down. “Leave? Why? People still live here, become sick. They need to be treated” he says. “Uranium was transported out of the mines on wagons and transported to Kara-Balta on the open road. High levels of radiation persist in storage sites today. They’re fine in other places.

He adds: “We can diagnose oncological illnesses at earlier stages now. Five years ago, Ming Kush came in fourth for oncological cases, now we are third. This is not because more people are getting sick, it is because of improved diagnostics.“

Nekrytov remembers a time when in and around the town the mountain slopes were black and the cliffs had no vegetation. Today they are green. “Nature has the ability to heal itself, one just should not disturb it. But mankind seems determined to spoil it,” the doctor says.

Some time ago Nekrytov started beekeeping. His honey is one of the best in the Naryn Region because it is surrounded by mountain meadows and juicy and healthy mountain flowers, herbs and shrubs. He even sells his honey to customers in Turkey, it is that healthy and fragrant. A particularity of Nekrytov’s apiary is that his bees do not roam: there is enough biodiversity for them.

Less and less ice

Eagle breeder Aman Ismailov calls Naryn a tourist’s paradise. “Water is more valuable than gold. We should not touch the soil, but develop tourism” Ismailov says. “Especially since there is less water now. In childhood we walked over the ice to the other river bank and played there. Now you can’t stand on the ice anymore because there are only a few small pieces on the river, that’s it. We used to drink water from the river but now we can’t, because a lot of trash is dumped into it. I have also noticed that there are fewer fish in the Naryn. The Osman fish caught are all small, 15-20 cm in length, and trout is rare.”

Ismailov is 40 years old, lives in Alysh village, trains golden eagles and holds salburun demonstrations for tourists. Salburun is an ecological way of hunting practiced by the Kyrgyz on horseback, with a bow and arrow, a Taigan hunting dog and a golden eagle.

Aman’s eagle, nicknamed Elmok, has already been world champion twice and won the Asian championships in 2018.

Veterinary doctor Satybaldy Imankulov has lived in the village of Kara-Sai in the Ak-Shyirak district, near the Chinese border, for two decades. In this time he and his wife raised four children.

“I notice the gradual shallowing of rivers and the melting of glaciers. As it is getting warmer, inhabitants have replaced their valeniki [felt boots] with ordinary boots, their fur coats with jackets. Yes, in this region the rivers freeze over completely during winter. The ice is up to four meters thick and it lasts until the end of June,” he says.

“But at the same time the snowfall is noticeably less,” Imankulov adds. “20-30 years ago they regularly cleared the snow and carried it away in vehicles. Now we do not have such snow. Of course it is easier for us, people living high in the mountains, to put up with less tough weather. Yet at the same time, a bit lower down the mountain, people have started to complain that in summer there is not enough water to irrigate their vegetable gardens at all.”

“I live in a place where multiple smaller rivers come together and all flow into the Naryn. Every 2-3 years the rivers change their course and the locals request the border guards for help to fix the river course,” he says.

According to Imankulov, there are 29 households in the district, which includes four villages, and a total of 57 people live there. School children do not live here, in the mountains, year-round, they go down for the school year. Only pre-school aged children live in the villages all year long. Adults live on animal husbandry, just like their grandparents and their ancestors before them. It is this way because of the severe continental climate.

“The locals depend on agriculture for their livelihood. Thanks to the clean waters in the upper reaches of the Naryn and the lush, ecologically clean variety of herbs and grasses the sheep, goats, cows and horses do not need antibiotics up here. A bit down below, it is compulsory to vaccinate livestock. Meat and milk products here are of the highest quality, we fish Osman fish in the rivers and that is why the people here are in excellent health”, Satybaldy Imankulov says.

“Look after the water!”

Edil Ashirov is also from Kara-Sai village. He breeds yaks and often spends time by the Naryn.

“Through distance learning I studied ecology, but I was always occupied with animal husbandry, with raising bulls,” he says. “Two years ago I started breeding yaks. I have two herds, one of 200 animals and one of 300. They graze on the Syrt highlands. It’s not a jailoo [summer pastures], it’s higher up, where it freezes 40 degrees below zero in winter.

“Yaks are undemanding and withstand such temperatures well. They walk around and fight it out on their own,” Ashirov explains, laughing.“Keeping yaks is the most ecological and unique industry, it is very profitable. Not only is yak meat valuable, so are yak milk, horns, hide and wool! I also like this place, it is so attractive for its beauty. Yaks do not like to stay in one place. One has to look after them because they can go far and run away, but on the other hand one doesn’t need to prepare hay for them! And I too have a strong nomadic spirit.”

Through years of observation Edil Ashirov has noticed that the climate is becoming more dry. There is less snowfall and rainfall is becoming rare. In addition, there has been a steady decline in the volume of water at the headwaters of the Kara-Say river.

Read more: A disappearing river: the fate of the Ural

“The people down below do not know about this, they think that they don’t get enough water due to some artificial obstacles,” Edil Ashirov says. “But the reasons are ecological: The rivers are fed by glaciers and snow and the glaciers are getting smaller. Local shepherds with more experience tell us that the volume of water in the rivers used to be larger, that people and cars could go underwater, that it was not easy to find a crossing. Yet now people can wade the rivers!”

Today not only adults know of climate change. Children do, too.

Young manaschi (oral storyteller of the Epic of Manas) Daniyar Koichubekov has lived by the river bank of the Naryn’s main tributary, the Kara-Unkur, since he was two years old. Now 12 years of age, Daniyar remembers that as a small child he was very afraid of going close to the water because of itsstrong current. In the past few years, the water has become much calmer.

Daniyar loves to sing about his beloved region, the land of the great hero Manas, who saved the Kyrgyz people’s ancestors. “I appeal to the current generation – protect the water, the most valuable gift to man, and keep it clean!”.

Sonunbek Kadyrov has a very direct relationship with the river – he is a ferryman.

“Like many other rivers in Kyrgyzstan, the Naryn is not navigable due to big height differences, difficult terrain of the riverbed and the speed of the water flow. But it is almost navigable,” Kadyrov says with a laugh. “This is because our ferry runs here and gives our ‘local islanders’ communication channels with the rest of the world!”

Two years of running a ferry and connecting the banks of the Naryn is a long time. Sonunbek makes an agreement with the locals for a year at a time and transports people, animals and goods on his boat, which he built himself. Close to Sonunbek is always his son, first-grader Ariel, who is always learnsing from his father.

Father and son know that their work is dangerous. There are many underwater currents, depth, cold water, but this work helps the family survive. And it helps the people: before there was a ferry, people crossed the water in boats themselves. It was difficult to row across the waters with oars, especially in a loaded boat.

Now there are fewer dangers, according to Sonunbek Kadyrov. He has noticed a sharp drop in the water level. The winds have increased, the mountain slopes carry less snow and the snow doesn’t stay as long as it used to.

But there are also times during the period of intense snow and ice melting when passengers have to scoop water from the bottom of the ferry right up until the moment it docks on the shore. There, their “taxi” is waiting for them: vehicles drawn by animals such as donkeys and horses.

From there, it takes two hours to reach the village of Kyzyl Beyit on horseback.

Kyzyl Beyit, cut off from the world

Kulchoro Ramanov, the head of the village, says that in Soviet times there were sovkhoz, communal farms, here. After perestroika, farming businesses came in their place. Many working-age villagers left to find work elsewhere in Kyrgyzstan, some abroad. Some houses have remained boarded-up. Young people come visit their relatives, but less and less often.

The elders have nowhere to go, and why would they leave anyway? “About 300 people are left. We mostly engaged in goat breeding. We collect goat milk, make goat cheese and sour cream. For winter we have to prepare fire wood and hay for the livestock. And we have to stock up on products from the bazar on the other riverside,” Ramanov explains. This is real subsistence farming: there is no school, hospital or electricity, aside from the renewable energy sources recently installed by international organisations.

“It’s only five kilometres from Kyzyl-Beyit to the hydropower plant but in reality it seems no closer than the moon! People have managed to fly there, but the government has not even bothered to connect our village to electricity! What internet or civilisation is there to talk about? The only joy is when the mailman brings us letters” Ramanov adds.

Mairambu Aidaralieva, a pensioner from Kyzyl-Beyit, has lived near the Zhaka river, a river which flows into the Naryn, since birth.

Aidaralieva says that she could never leave this place: it’s beautiful, the ecological situation is good, there are many medicinal herbs, springs, and the memories of her ancestors. She collects herbs and dries fruits and berries. “From the river we get trout and marinkas. Thanks to Allah, we have enough drinking water and soon, even electricity. Where would I go?,” she says.

Mairambu Aidaralieva and the other locals talk about the changing climate, citing the water levels in the rivers and the weather changes. She says: “The weather has changed significantly; it has become unpredictable. It has become very cold in winter and the winds have become stronger. We have heavy snowfall on our island, while in other places they complain about having too little snow. The Naryn river has become more shallow. And this is our most important river!“

Village elder Emilbek Aitbaev from Kyzyl-Beyit remembers a story told to him by his elders: “In Russian, Kyzyl Beyit means ‘Red Grave’.”

“A long time ago, Kyrgyz came here after bloody battles which took many young lives, and settled down. The first thing they did was to bring drinking water, it is the most basic necessity. And then they started planting trees. This was bequeathed to us by those who lived here before. So I now instruct my grandson Nurbolot and those who will live after me in those ways. I am an old man, but I still plant trees.”

He concludes: “We are simple people, we live simply and in harmony with nature according to the instructions of Manas. We do not leave this land because there is nothing waiting for us in the cities and towns. They know that they elect presidents and deputies, and they promise us a lot of good- light, roads, a decent life! But what do we see? We live as we know how to and do not expect anything from them. The only trouble is that when it snows and it is freezing, it is dangerous to go near the river, to the water. Then we are completely isolated from the outer world. If only they would help us build a pier.”

The people of Kyzyl-Beyit live on the Naryn river the old way, retaining their singularity and used to managing without electricity.

“We must think of the future!”

Uyalkan Satarova, shift supervisor at the Toktogul hydropower station, calls the Naryn a source of light.

Satarova grew up in a family of electricity specialists. Her husband is also a power engineer and both her son and daughter are studying to become power engineers in Bishkek.

“The river has significant energy resources: There are large hydroelectric power stations in Toktogul, Tash Komur, Uch Kurgon, Kurpsay and Shamaldysay. They are planning to build the Kambartinski hydropower station and a barrage from the upper Naryn hydropowerplant with the accompanying reservoirs,” Saratova explains.

“The generation of electricity depends directly on the water in the Naryn. In the long run, a reduction of water available for hydropower is inevitable. If the water level of the river falls then less water goes through the dam, and this will reduce electricity production.”

“This has consequences for the neighbouring countries and can have an influence on diplomatic relations with them. For Kyrgyzstan itself, a reduction in water will mean that the country has to buy electricity or coal from its neighbours. Renewable energy sources could be the answer,” she adds.

The director of the museum of the Toktogul hydropower plant Sabirzhan Toktogulov can spend a long time talking about the Naryn.

He explains: “It is calm and unhurried in the plains, but in the mountains it seems to go crazy and has a lot of potential energy! The river has a drop of 1,715 metres with an average gradient of 3 degrees and is almost as strong as Europe’s biggest river, the Volga, in terms of water power. The Volga has a capacity of 6.20 million kilowatts and the Naryn 5.94″

Now a pensioner, Sabirzhan Uezbaevich Toktogulov came to Karaköl, near the Toktogul Reservoir, in 1974 on a Komsomol trip and lives here to this day. He embodies the history of hydropower in Kyrgyzstan.

“In April 1962, the first hydraulic engineers came to build the Toktogul hydroelectric power station with one dream – to see a light bulb light up with their help, to see people getting electricity. What they created is still alive today,” Toktogulov says. “But climate change is already proven. This means the future of Kyrgyz hydro-power is in jeopardy. We need to think of the future!”

Toktogulov tells of what he has been observing for almost 40 years: “The glaciers are melting, and today we have to collect water. Under the planned Soviet economy there was order and a scientific approach, but today the unplanned economy has led to soil erosion, degradation of pastures, there are too many herds for the available pastures. All this aggravates climate risks. Decision-makers talk a lot making the economy green, but that progress is faltering.”

Scientists agree with the conclusions of Toktogulov and others living near the Naryn River.

If in the 1960s Kyrgyzstan had about 8,200 glaciers, climatologists predict that by 2100 only 142 to 1,484 glaciers will remain. Their volume will shrink by a factor of ten. “We have detected serious climate change in Kyrgyzstan. It has already been recognised as one of the most climate-vulnerable countries in the area. This is largely because of a high dependence on glacial melt water,” said Nicolas Muliniu, a UNICEF consultant on climate change.

Climate change can no longer be stopped completely, but it can be slowed down and this is the only possible way both for Kyrgyzstan and for the other countries of the region that depend on each other for water.

More photos can be found in the original article.

Тhe project “Developing Journalism: Exposing Climate Change” aims to identify the challenges of progressive climate change through the development and strengthening of independent media in Central Asia under the mentorship of experts from Media Development Center in Kyrgyzstan, Anhor.uz in Uzbekistan, Asia Plus in Tajikistan and Vlast.kz in Kazakhstan. The project is implemented by n-ost (Germany) and MediaNet International Centre for Journalism (Kazakhstan) with the support of the German Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ).

Vlad Ushakov, Irina Bairamukova, Gamal Soronkulov

Translated from Russian by Nora Heinonen

For more news and analysis from Central Asia, follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Telegram, Linkedin or Instagram.

Life by the river: the Naryn in Kyrgyzstan

Life by the river: the Naryn in Kyrgyzstan